|

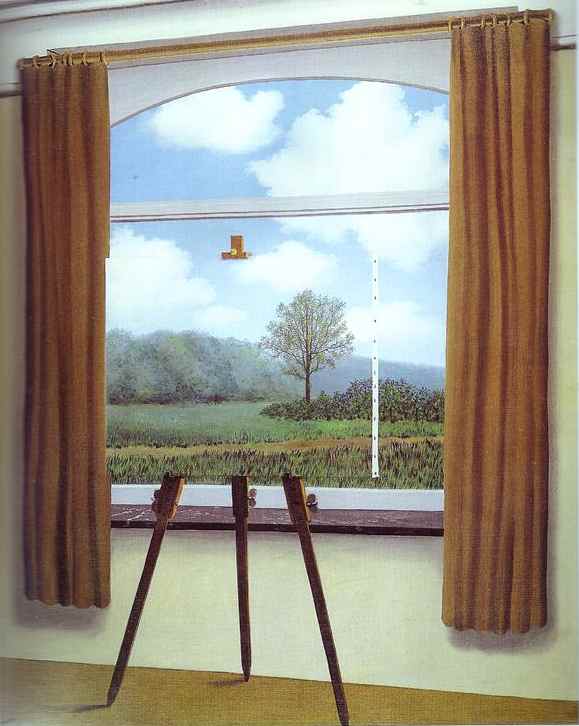

| Magritte: Follow Your Brain

I have found little interesting analysis of this Magritte painting in art criticism. There is only one question we can ask ourselves: what does it mean? The following often quoted remark by Magritte should be disregarded: When one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself “What does that mean?” This is utter rubbish, and typical self-misunderstanding on the part of an artist. Bad translation too. Most of Magritte’s pictures have very clear meanings to them, though Magritte goes to certain lengths to obscure those clear meanings. As it is with so many artists, we must disregard the artist’s own interpretation of his work. Self-interpretations are more often subconsciously designed to mislead. Magritte would try to argue, based on the quotation, that The Human Condition I has no meaning because it presents a mystery, and mystery, because it is unknowable, is meaningless, therefore the painting is meaningless, but still worthwhile somehow. This is all a compensation move on the part of Magritte resulting from the artist confronting the naked didacticism (preachiness)of his own work, and not being able to accept it. Magritte wrote retrospectively about his art, after time to think, but he is self-interpreting well before that. Following the surrealists, Magritte found he could self-interpret through titles. Magritte’s titles are a clue to his one weakness: he tries to compensate. Like other modern artists, he uses titles as deflectors, chosen to enhance mystery, to artificially widen the implications of an image. Magritte’s fun with titles conveys his underlying anxiety: my pictures are not modern enough. They are too good, too universal, too classically artistic, too innocent, too thoughtful, too meaningful. To be modern is to be ugly and shocking on the surface. Magritte can be ugly and shocking, but his purism as an artist forces him to take the difficult route of embedding the ugliness and shock-value beneath the surface, where it is revealed to the viewer through a mental step taken in the interpretation process. Magritte anticipates our brain-moves as interpreters. That’s how good he is. He expects us to care enough to think, but he’s not an asshole about it, which is also un-modern on his part. He lacks the assholeness of a Picasso, and therefore usurps Picasso, and exposes Picasso as a man lacking in brain. The most un-modern aspect of Magritte’s art is the simple fact that he makes it mental, makes it difficult for himself by setting a high intellectual bar. In the age of Gertrude Stein and Henry Miller, it was okay for artists to lack inventive powers, to be, frankly, uninspired. Magritte rejected that, and if he rejected the surrealists it was because they were about finding ways to cheat, to fabricate inspiration through drugs or whatever. Magritte maintains a certain un-modern idealism. The process of his art involves the daunting first step of inventing an interesting visual or intellectual concept. The difficulty of continually inventing such concepts and ways of presenting such concepts poignantly through the medium of painting explains why Magritte would paint slight variations of the same idea three or four or ten times. As a painter, he must paint, and better to reinterpret a good painting than resort to empty-headed improvisation, as a lesser artist would. The whole idea of Magritte’s lofty ambitiousness to be deep, to be impersonal, to make art cerebral, to be strictly mental in a sexualized world by itself lifts him out of his art history categories. Not only is he not a surrealist, he is not even a modernist in my view though he tries to be. All that’s modern about his work is the titles. No matter how good the painting is, calling it The Human Condition is exactly as pretentious as you think it is, and exactly as wrong artistically. But remember why he’s doing it. Aesthetic flaws are psychologically revealing. Calling it “the human condition” is an attempt to mute the attitude of the painting, and is clearly intended to imply a sage acceptance of the scene on the part of the artist. There it is, a painting in front of a window, that‘s just how we are. But don’t be fooled. Magritte is outraged by this image. The fact is this painting is a sermon on art consisting of a three word slang question: “What’s the Point?” First of all, this work does not, as some unthinking pedants would spew, make us question the reality of the external world. No. What it does do is force us to accept the copiableness of the external world. Magritte’s work overall, and in this painting specifically, shows painting can be photographically accurate in its rendering of any object or any landscape. That is the powerful factuality of Magritte’s work. Impressionists are wrong to justify their work by saying the eye does not see the world in sharp detail. That’s absurd. The eye does see in sharp, intricate detail. Magritte’s so-called “triompe l-ieul” style is simply his decision to be utterly honest in his depiction of how detailed the eye is in its perception of space and shape in the world. This honesty translates visually as objectivity, or a lack of emotion. As a painter, Magritte agrees to devolve from human to camera. But by doing so, he focuses attention on himself as a painter who thinks first, renders second. Saying: thinking matters most. Thinking matters most. I’m glad I said that. Because that is another way of phrasing the gist of Magritte’s The Human Condition sermon. The sermon is a plea in defense of Magritte’s kind of art. It pleas by asking a simple question: Why paint a landscape? If you want to look out the window, look out the window. This goes back to Plato’s argument that we don’t need art because it is “thrice removed from the truth.” Magritte sides with Plato: ideas are eternal, and can be viewed in original form only in the imagination. Why make a copy of a copy? Why look at the copy of a copy if the copy is right in front of you? That Platonic pointlessness is what Magritte shows with that white sliver of the side of the tacked-in canvas and the view-obstructing easel. Why have that there? Just get the painting out of the way. That is if you really want to look out the window. Do you? Oscar Wilde said a gentleman never does. Why would he say that? For the same reason Magritte would say it - there’s nothing to see. Magritte shows a subdued, random, murky country landscape, almost a parody of nature. Not very inviting. Better to stay inside. Wilde again: “I detest all nature where man has not been with his artifice.” Magritte says so also through this image. Nature, the god of formlessness and randomness, is anti-art, therefore the artist must be anti-nature. Not only does Magritte sermonize against landscape painting. He sermonizes against nature itself. Nature does not arrange properly. Man must help through mind. Suzi Gablik writes, “In this single image [Magritte] has defined the whole complexity of modern art - a complexity which has led to the devaluation of the imitation of nature as the basic premise of painting.” Ms. Gablik uses the word “complexity” like this in an attempt to superficially specify vague thinking. But she is exactly right. He defines the post-photography art painting conundrum in a single brilliant image. But focus on the aesthetic message it sends. Magritte says to artists: don’t just paint. Think. Use your skill as painters not to stylize objects, not to experiment with color and light, but to define crises, to understand psychology, to invert nature. Follow your brain. I’m glad I said that too, because THAT would be a far more appropriate title not just for this but for many of Magritte’s pictures: Follow Your Brain.

|

| Back |

© 2005 The Drawers